What makes us human in the future of work

Opportunities are for humans to grasp, skills are for humans to learn, policies are made for humans.

My last article discussed how the advent of technology is reshaping the importance of ‘place’ and ‘skills’ in a worker’s identity. Now, what does this mean for us as humans and not just as workers?

To examine this question we must look at other factors impacting ‘Future of work’ and they are – Unequal distribution of income growth for individuals represented by the Elephant curve, Family structure, Increasing life expectancy and Climate change.

What the Elephant curve says about the future of work

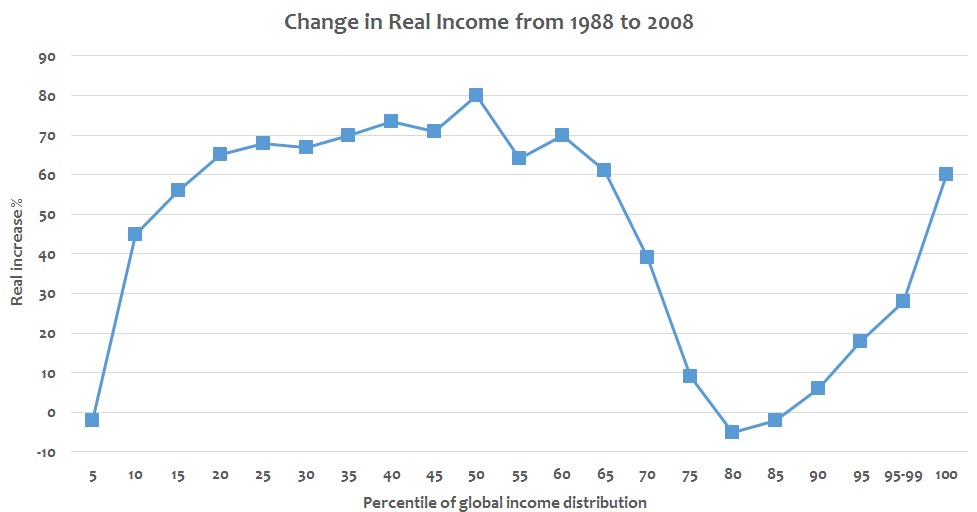

The Elephant curve, as shown below, was created by Christoph Lakner and Branko Milanovic to illustrate that there is an unequal distribution of income growth (1988 – 2008) for individuals belonging to different income groups – Poorest citizens, Global middle class, Global upper middle class and Global elites.

There were four main conclusions drawn from the ‘Elephant curve’ in relation to globalisation’s effect on income inequality:

1. Those who gained nothing

Beginning with the tail portion of the graph, in the past two decades the very poorest citizens of the world experienced almost no benefits from the rise of globalization. This reflects the low growth that has occurred in the poorest countries, specifically countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).

2. Those who gained a little

The middle section of the graph, from the 10th percentile to the 50th percentile, represents the global middle class. The growth that occurred in this section of the population reflects the fast economic growth of many countries that were once considered “developing countries” such as China and India.

3. Those who lost almost everything

The sharp downward curve that resembles the downward slope of the elephant’s trunk represents the global upper-middle class corresponding to the working and middle class of richer countries. This class experienced little to no growth in wages during globalisation in the years between 1988 and 2008.

4. Those who gained the most

Lastly, the upward sloping part of the graph that resembles the tip of the elephant’s trunk represents the ‘global elites’ who experienced tremendous growth as a result of globalisation (1998-2008).

Of these global elites, those belonging to the top 1% have had a notable increase in income growth, which has led many, including the creators of the graph, to deem the top 1% as the “winners” of income growth due to globalisation.

What happened with income inequality in the poorest group?

The factors that placed Sub-Saharan Africa at the bottom of the Elephant Curve during 1988 – 2008 were poor infrastructure, low industrialisation, and weak governance. These factors are still relevant today for many countries in the region except South Africa, Kenya and Nigeria. Further, the region's share of global GDP remains small, with limited participation in higher-value global supply chains.

The other set of data suggest that agriculture employs more than 50% of the workforce in Sub-Sahara Africa’s. The farm mechanisation, precision farming, and agri-tech solutions may take away employment from those who are sitting at the beginning of the tail portion of the Elephant curve. In addition, Sub-Sahara Africa's 85% workforce is predominantly informal labour (involves economic activity that is not registered, regulated, or protected by existing legal or regulatory frameworks). Without offering immediate alternative employment, bringing in large scale automation may disrupt informal jobs (e.g., street vending, small-scale farming) without offering immediate alternatives, which may lead to economic instability in the region.

But, why is the impact of ‘unequal distribution of income for individuals’ so important?

If we look at the income inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa, we see how it reduces access to quality education and skills training, particularly for low-income groups. It results in a self-perpetuating skill gap, underemployment and heavy reliance on informal and low-wage jobs.

Further, income inequality reduces overall economic demand, as lower-income groups lack purchasing power and its impact can be seen in slower growth which limits job creation, especially in high-growth sectors. To summarise, the income inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa poses significant challenges to the future of work by limiting access to opportunities, perpetuating informal economies, and hindering economic growth.

The link between family structures, life expectancy, climate, and work

Research has found that there is a strong connection between family structures and the ‘Future of Work’. Today’s changes in family dynamics, cultural shifts, and the evolving needs of modern families significantly impact how work is structured, perceived, and performed.

For example - smaller family units and single-parent households often require more flexible work arrangements to balance caregiving responsibilities. In response to this need, enlightened employers are increasingly adopting policies like remote work, flexible hours, and parental leave to accommodate these needs. In the Nordic countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland), the shared parental leave policies encourage fathers to take an active caregiving role. In addition, with shifting norms around caregiving, more men are participating in child-rearing and household duties, leading to demand for gender-neutral policies in the workplace.

Then, we see the emerging trend related to life expectancy – as the life expectancy increases, families often need to care for elderly members, creating demand for eldercare benefits and workplace support. Interestingly, jobs in the healthcare and eldercare sectors are expanding as a direct response to this trend.

Last but not the least, there is a strong connection between climate change and the ‘Future of Work’, as the global shift toward sustainability will reshape industries, job markets, and workplace practices. Climate change impacts the future of work in the following ways:

The transition to a low-carbon economy will create millions of jobs in renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, electric vehicles, and environmental conservation. For example - Solar panel installation, wind turbine maintenance, and carbon capture technology. It is interesting to note that according to the International Labour Organization (ILO), a shift to green economies could create 24 million jobs globally by 2030.

In addition, workers in fossil fuel industries will need to transition to green sectors, requiring large-scale reskilling programs. Similarly, sectors like manufacturing, transportation, and construction will need to adopt sustainable practices, leading to shifts in job roles and skill requirements. For example - engineers may need expertise in sustainable materials and energy-efficient processes.

It has also been projected that data scientists, software engineers, and climate modelers (climate carbon analysts, forest biometricians, argo-meteorologists, etc) will play a vital role in creating and implementing solutions to mitigate climate change.

What all this means for us as humans

As we have seen, the factors that fundamentally impact the ‘Future of Work’ are creating many opportunities for new industries and roles, and reshaping the way we think about and do work as individuals and communities.

These factors also highlight the greater need for acquiring new skills, reskilling, policy innovation, and ethical considerations to ensure a fair and sustainable transition.

We cannot and must not forget that opportunities are for humans to grasp, skills are for humans to learn, policies are made for humans. The entire transition into the new world of work is about elevating humanity. How we navigate the ‘Future of Work’ and what outcomes we see will be deeply intertwined with how societies address the imminent challenges by keeping humanity at the centre stage.

Elephant curve illustration: Farcaster, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0