Kancha Gachibowli deforestation: When will IT infrastructure stop costing us the planet?

In a time when cities across the globe are grappling with rising temperatures, toxic air, and the slow disappearance of green spaces, the Telangana government’s decision to auction 400 acres of pristine forest in Kancha Gachibowli, Hyderabad, lands like a blow to the very lungs of the Earth. These are not just trees being cleared for concrete; this is the dismantling of an ecosystem that has stood silently for centuries—absorbing carbon, sheltering wildlife, nurturing water bodies, and offering serenity in a city increasingly suffocated by its own expansion.

The state’s rationale? Economic growth through IT park development. And to be fair, the IT sector has been a powerful engine of India’s transformation. Hyderabad, in particular, has risen as a global tech destination—home to industry titans like Microsoft, Amazon, and Google. The sprawling IT parks of HITEC City have generated lakhs of high-value jobs, boosted exports, attracted foreign investment, and helped the city earn a place on the global innovation map. For policymakers, such success stories are compelling, representing progress, opportunity, and global relevance.

But bulldozers tearing into this living, breathing expanse of forest aren’t just clearing land—they’re carving into our future. Can a few more glass towers truly replace what this forest gives us? Can digital progress ever compensate for the loss of biodiversity, clean air, and climate resilience?

Kancha Gachibowli stands as one of Hyderabad’s last remaining urban forests, a verdant expanse teeming with biodiversity. This area is home to approximately 237 species of birds and a variety of wildlife, including spotted deer, wild boars, star tortoises, and snakes such as the Indian rock python and cobras. The presence of Peacock Lake and Buffalo Lake further enhances its ecological significance, serving as sanctuaries for migratory birds and supporting aquatic ecosystems. The dense vegetation plays a crucial role in air purification, carbon sequestration, and groundwater recharge—contributing significantly to the city’s environmental health.

So, when did it all start?

The conflict over the Kancha Gachibowli forestland has unfolded over several years, revealing a deep and ongoing clash between Telangana’s industrial ambitions and the urgent need to preserve Hyderabad’s fragile ecological balance.

Early 2000s to 2010s: The forested land adjacent to the University of Hyderabad (HCU) remained largely untouched, acting as a biodiversity-rich green buffer. Over time, however, its proximity to the city’s expanding IT corridor drew increasing government interest in leveraging the area for real estate and infrastructure projects.

2016–2019: Concerns mounted as construction activity around the forest picked up. HCU raised repeated alarms about encroachments and environmental degradation. Students and faculty began advocating for the protection of the forest as integral to the university’s ecosystem and academic environment.

2022: The Telangana High Court ruled that, in the absence of a deed of conveyance, the 400-acre forest tract remained government property. This landmark judgment tilted the legal balance in favour of the state. Nevertheless, the University of Hyderabad continued to claim that the land was part of its designated campus and an essential ecological zone.

2023: The Supreme Court upheld the High Court's decision, reinforcing the state's legal authority over the land. This development set the stage for accelerated government plans to repurpose the forest for commercial use. Environmentalists and academics feared that legal backing would pave the way for deforestation without adequate consultation.

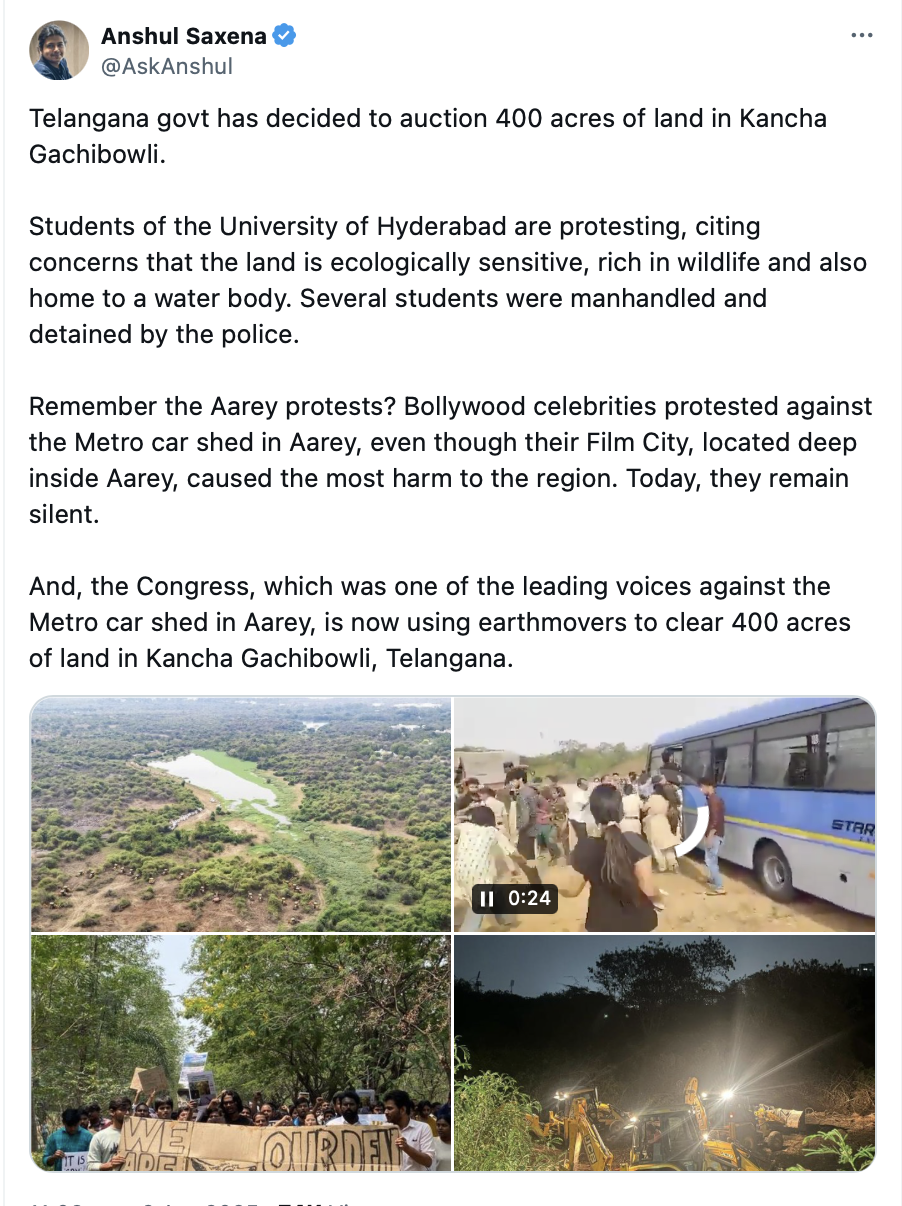

Early 2024: The Congress-led Telangana government handed over the land to the Telangana State Industrial Infrastructure Corporation (TSIIC) to initiate an IT park project. Bulldozers entered the site under tight police protection, triggering student protests and widespread criticism from civil society. Protesters accused the government of ignoring environmental norms and forcibly occupying land without transparency.

March 2024 – March 2025: Despite mounting opposition, reports emerged of ongoing tree-felling and land clearing. Activists filed multiple Public Interest Litigations (PILs), urging courts to grant the land “deemed forest” status under the Forest Conservation Act and to halt development activities. The government, however, continued to push forward, with little indication of conducting an environmental impact assessment or public consultation.

April 2025 (Current status): The Supreme Court has intervened, ordering an immediate halt to tree-cutting and excavation in the Kancha Gachibowli area. The court expressed concern over the ecological damage already caused—nearly 100 acres cleared, with wildlife such as peacocks and deer affected—and demanded a site inspection and an explanation from the state.

Public outcry and legal resistance

The state’s decision to clear and auction 400 acres of forest in Kancha Gachibowli has ignited an intense public backlash. What began as student-led protests on the University of Hyderabad campus has since grown into a broader movement, drawing in environmental groups, civil society organisations, nature lovers, and concerned citizens across Hyderabad.

At the heart of the resistance is a deep sense of betrayal—that in the name of development, the government has ignored public consultation and environmental safeguards. Protestors have rallied under banners like “Reclaim Our Land” and “Reclaim Our Rocks,” referencing the area’s rich biodiversity and unique rock formations.

The forest, home to over countless species of birds, spotted deer, boars, and even the endangered Indian rock python, is seen not as wasteland but as a vital ecological lung for the city.

The recent Supreme Court directive in April 2025 to halt all tree-cutting and excavation has been a rare legal win for protestors, offering temporary protection while the court seeks further explanation from the state. The ruling came amid reports that nearly 100 acres had already been cleared, displacing local wildlife and destroying habitat.

The folly of repeating mistakes

Bengaluru’s tragic transformation from India’s beloved “Garden City” to a cautionary tale of unchecked urban expansion offers a stark warning for Hyderabad. Once adorned with a pleasant climate, abundant lakes, and a lush green canopy, Bengaluru is now choking on its own developmental excesses. According to a 2020 study by the Indian Institute of Science (IISc), the city lost 93% of its vegetation and 79% of its water bodies between the 1970s and 2016.

Today, with over 10 million residents and crumbling infrastructure, it faces acute water shortages—with private water tankers now forming an essential lifeline as borewells run dry. In March 2024, parts of the city reportedly faced 20-hour water cuts, forcing citizens to buy water at exorbitant rates. The root cause? Unrelenting real estate development and infrastructure projects that prioritised concrete over canopy.

And Bengaluru is not alone. Across India, the pattern is alarmingly familiar. In Uttarakhand, nearly 10,000 trees were felled between 2018 and 2023 for highway expansion projects in fragile, landslide-prone terrain. In Mumbai, the cutting of over 2,000 trees in the Aarey forest for a metro car shed prompted massive citizen protests and legal battles over ecological rights. Goa, too, has witnessed strong resistance from local communities against deforestation in the Western Ghats—one of the world’s eight hottest biodiversity hotspots. These projects, often masked as progress, have led to increased flooding, loss of wildlife habitats, and greater vulnerability to climate extremes.

Hyderabad now stands at a similar crossroads. If it sacrifices the 400-acre forest in Kancha Gachibowli—one of its last remaining ecological lungs—for IT infrastructure, it risks repeating the same mistakes. The cost won’t just be measured in lost trees but in vanishing wildlife, disrupted local ecosystems, and a city struggling to breathe—both literally and figuratively. Is this the development we truly want?

A call for sustainable alternatives

The outcry underscores the need for a paradigm shift in development planning. Sustainable alternatives must be considered, such as:

-

Brownfield development: Repurposing existing underutilised industrial sites can accommodate new IT infrastructure without encroaching on ecologically sensitive areas.

-

Vertical expansion: Encouraging vertical growth can optimise land use, reducing the need for extensive land acquisition.

-

Integrated green spaces: Designing IT parks with substantial green spaces can mitigate environmental impact and promote biodiversity.

True development must harmonise economic objectives with environmental stewardship, ensuring that growth does not come at the cost of ecological degradation. Hyderabad stands at a crossroads: it can either heed the lessons of cities like Bengaluru and choose a sustainable path, or it can proceed with actions that may yield immediate gains but result in long-term losses. The choice is clear, and the time to act is now.