Should the CHRO become part of a Chair-CEO-CHRO SuperTrio?

This is the third of three articles looking at the human relationships between the Chair, the CEO and the CHRO. In our research for these articles we sensed a strengthening of our hypothesis around both the importance of this trio and the relative paucity of debate about it. And as this realization began to dawn, we decided to try to improve our understanding of these critical organizational dynamics and take things deeper.

In this article, therefore, we examine the three relationships as they interact at a granular, and sometimes painfully, human level. We consider what happens when the nature, degree and intensity of the triadic relationship suffers dysfunction or is sub-optimal. Finally, we offer up some positive suggestions which we hope will create some optimism for the future of this valuable group and their contribution to organizational life.

What we know so far…

In recent years, former Harvard Professor, Ram Charan, has spoken about the need to elevate the CHRO role to be on a par with that of the CFO:

In most companies, there is a rigor about the financial side, but numbers don’t drive the company, people do.” (Menon, R. (2018))1

Professor Charan also shares his belief that it is important for CEOs and CHROs to bond. There must be strong trust for the relationship to succeed - along with respect for each other’s judgment. Only then can CHROs “position themselves as partners and constructive challengers” and help the CEO with the many people-centred challenges faced by the business.

In their white paper, “Why Now Is the Time to Have a CHRO on Your Board”2, authors Magsig and McGrath write that:

Without a forward-looking human resources plan, a subset of the business strategy designed to maintain and engage the people required to execute the strategy at every level, even the best strategy is of little use.

Given today’s turbulent economic environment, businesses need to pivot and transform faster than ever before. The CHRO not only has to keep up – but in fact, stay ahead of the game. The CHRO needs to be totally on top of a range of critical people issues - such as ongoing succession planning for all mission-critical positions. (This would include the CEO and all executive positions and those tightly connected to the central strategy of the business). This is but one of the many things the CHRO needs to pulse-check constantly, ensuring that strategy and culture are both kept top of the agenda.

Magsig and McGrath also quote the Harvard Business Review:

Strategy and culture are among the primary levers at leaders’ disposal in their never-ending quest to maintain organizational viability and effectiveness …. When aligned with strategy and leadership, a strong culture drives positive organizational outcomes. (Groysberg et.al. (2018))3

Given that many Board members have not been exposed to top-performing CHROs and have not had the experience to deal with the kind of complexities habitually handled by a world-class CHRO, the authors posit that it is time to get CHROs onto the Board:

Having a CHRO as a director would help ensure that these critical issues are addressed and managed regularly by the Board. (Magsig, M & McGrath, J (2019))ii

It is interesting to observe that in this white paper and in other similar articles calling for CHRO involvement with the Board, little if any comment is ever made about the relationship between the Chair and CHRO. It seems to be left largely to itself, quietly overlooked. We do know though, that much is written about the importance of the Chair-CEO relationship as noted in our earlier article. The references to the CEO-CHRO relationship that have however surfaced are often made in connection with the recognition of the growing importance of culture in organizations – and the linking of both roles (CEO and CHRO) to the question of how organizational culture is shaped and influenced.

In an interview with Professor Patrick Wright of the Darla Moore School of Business, University of South Carolina, conducted by ThePeopleSpace (UK), findings from Professor Wright’s latest CHRO study were shared. Among the results, culture is shown to be rising up the ranks of priorities for CHROs.

Organization culture is back in vogue. But not for all the right reasons. Whether it’s the #MeToo movement, staff fabricating bank accounts to meet their goals at US financial services multinational Wells Fargo, or the harassment and discrimination at Uber, a toxic company culture has been to blame. (Harrington, S. (2019))4

Which means that Boards are feeling the heat, not just the CEO and CHRO. And unsurprisingly, the result is that Boards are focusing more on understanding culture – which in turn makes them question what the CEO and CHRO are doing about it.

So who’s supposed to be in charge of 'culture'?

The key roles involved in shaping 'culture' are recognized as being Chairs, Board Directors, CEOs and CHROs. There seems to be general agreement that CEOs need to “own culture”, while CHROs understand that “managing culture” is part of their remit. Board Directors often view culture through the lens of mitigating risk - though some, according to Professor Wright, “…are starting to become much more focused on culture, as they believe that a positive culture can lead to better customer service and a better customer experience.” “But,” he adds “Do they actually know what the culture is in terms of the espoused values, how real is it in the organisation and what is the company doing to manage it?” (Harrington, S. (2019)iv). “Finally, an area of CHRO, CEO and Board alignment: Culture”).

So, one thing is clear: there is without question a meeting place for these three roles – Chair, CEO and CHRO – and central to that meeting place, amongst many issues, is culture.

In light of this, let’s look at these relationships in more detail.

Under the microscope: the Chair-CEO-CHRO (The SuperTrio)

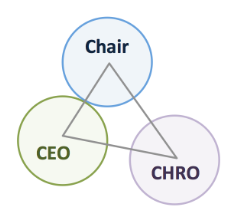

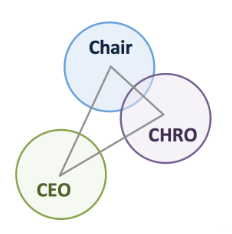

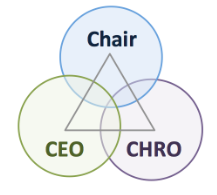

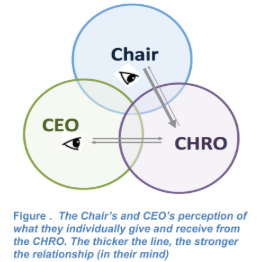

To explore the relationships between the Chair, CEO and CHRO further, we examined a range of different scenarios that might result as an outcome depending on how close or distant their respective relationships were from each other, using a diagrammatic convention, The SuperTrio Model©, to illustrate our interpretation of what can happen as the trio interact.

In our diagrams, the circles indicate the person’s (working) relationships. We consider three scenarios:

- When their respective circles do not touch, this denotes a distant relationship where there is no engagement, if any. The chances are that their working relationships do not overlap either. The key word to describe this sort of relationship is “transactional”.

- If the circles touch, this is an indication of perhaps a cordial relationship. In reality it may indicate that interactions tend to be limited to set-piece meetings only.

- If their circles are overlapping, this is an indication that they comfortably bring others into their discussions - and that their own relationships are close.

In all cases, depending on the combination of types of relationships, the different business scenarios represent opportunities for growth (or improvement). They also imply risk too, should there be inaction.

Let’s take a look at two potential examples.

Example One: CHRO out in the cold?

In this example, the Chair and CEO have a cordial and friendly relationship, but neither is close to the CHRO, for whatever reason (See Figure 1). In this scenario, some of the following situations may play out:

- Given the cordial and friendly relationship between the Chair and CEO, they may not ever have spoken much about the CHRO, nor thought to involve him much, nor perhaps do they see the CHRO as particularly relevant.

- They may doubt the CHRO is up to a standard whereby he could be helpful with issues surfacing at the Board level.

- They may not in fact trust the CHRO that much, and because of their own cordial relationship, conversations with the CHRO involving both Chair and CEO - for the most part - just don’t happen.

- The CHRO may lack the capability to assert himself or even build the necessary bridges with the CEO and Chair and

- The CHRO for his part may not see his role stretching into issues debated at the Board.

- And as far as the Board is concerned, the CHRO simply fades into the background.

The risks of inaction in this scenario would be:

- Firstly – a lost opportunity to bring the CHRO into the many people-related conversations that both the Chair and Board would need to have - as well as the chance to work closely with the CEO in the business.

- Secondly, there would be lost opportunities for the Chair and CEO to have frank, timely and useful conversations - should their relationship never develop beyond the “cordial and slightly removed”.

Opportunities for growth – it is probably incumbent on the CEO to make the first move to bring the CHRO into the conversation.

- The CEO will need to “fly the flag” for the CHRO and look for opportunities to strengthen the personal brand of the CHRO.

- Some of the actions we listed in our second article would go a long way to boosting the standing of the CHRO:

- The CHRO should invite challenge by the CEO and Chair so as to learn how to hold a point of view and how to present it in the face of opposition (and at the Board level), while also learning how to listen carefully to those with counter views.

- Given that CHROs often have to be the custodians of organisational rules, processes, and procedures, CHROs should invite the CEO specifically to challenge them around any tendency they might have to be judgmental.

- Trust. The CHRO has to develop trust across the organisation and that means developing a trusting environment and gaining the trust of others. The starting point needs to be the CEO and the Chair.

- In our experience, a Chair and Board that does not trust the CHRO of the organisation will (metaphorically) simply cast them aside. As Chair, you can help avoid this by making a point of checking in with the CHRO from time to time (and not only when there is a Board meeting), and

- Challenge your CEO to look for ways to bring the CHRO into the conversation and enable wider exposure for him.

Example Two: Heading for trouble

In this example, the Chair and CHRO have a good working relationship and the CEO is more distant from them both (see Figure 2). This scenario may have been created, and ultimately play out, in the following way:

- The Chair and CHRO have worked closely together as they managed the CEO search, recruitment, and appointment together.

- The Chair and CHRO may even have worked together in another organization and/or have some shared past, a particular way of working together or something similar.

- It may be that the CEO prefers to keep the Chair at arm’s length and doesn’t see spending time on a relationship with the CHRO as a top priority amidst other competing priorities.

- The “interaction gap” and the resultant “information gap” between the CEO and the Chair/CHRO can allow unhelpful narratives to emerge in the rest of the organization, leading to the creation of alternative realities and an erosion of trust.

- Over time, the CEO may be deemed a non-performer or have a difficult or derailing personality that makes everyone (including the Chair and CEO) maintain their distance.

- The CHRO in particular may decide to minimize interaction/disassociate themselves in anticipation of problems ahead, resulting in a widening of the “gap” and rapid deterioration in confidence levels.

The risks of inaction in this scenario would be:

- Gaps in communication and understanding can start to appear as the CEO starts to feel undermined by the apparent closeness of the Chair-CHRO relationship.

- As the CHRO starts to feel the CEO becoming ever more distant and mentions this to the Chair, the Chair starts to think the CEO is losing the confidence of the CHRO.

- The Chair and the CEO find it difficult, if not impossible (by this time) to have a frank, open and honest discussion. Likewise, the CEO may also feel the same.

- Things start to get ugly and eventually, the CEO resigns, or the CEO tries to fire the CHRO and runs into a brick wall (the Chair).

- In the end, everyone loses, including the company.

- Trust is eroded in the Board and in the company. It’s an unholy mess!

Opportunities for growth and mutual benefit

- The Chair and the CHRO need to work hard at the CEO relationship.

- Between them, they should try to discover ways to set the CEO up for success (perhaps through coaching or safe-space feedback).

- The Chair could take a more active role especially in the early days of the CEO’s tenure to help to “prep” the CEO in advance of Board meetings.

- The CHRO can provide back-up to the CEO by ensuring that they help by being the eyes and ears of the organization. They should ensure that the CEO is appraised of what’s going on – and to share good news as well as bad!

- At the same time, the Chair and the CHRO have a duty of responsibility to reflect on how they interpret given situations and how they behave in front (and behind the back) of the CEO – all to ensure it is not they who are the problem!

So what would a good trio look like?

Imagine a world where healthy and constructive relationships were enjoyed by the Chair, the CEO and the CHRO. Issues would be openly discussed, difficult conversations would not be avoided, strong opinions could be aired – and all while holding and maintaining healthy relationships. Roles would be respected, and clear boundaries would have been established.

Scenarios leading to the creation of a strong and high-performing trio might include:

- Coming through an existential crisis for the organization successfully – an experience requiring close and regular interactions.

- Other non-existential crises requiring a coordinated response (adverse media coverage, a senior leader has misspoken, a major accident or environmental issue has needed to be managed successfully).

- The members of this trio are seasoned leaders who all appreciate the need to work from a solid base of having healthy relationships with important roles. They “walk the talk” around the significant leadership development work their careers have embraced.

Inherent risks may include:

- Relationships becoming too close or familiar: over-stepping professional boundaries.

- Straying from their roles and unwittingly influencing decisions in an unhelpful way.

- Behaviors may be misinterpreted and lead to mistrust.

- Blaming of the three-member group: this may arise if things are going badly in the organization, and the CEO, Chair and CHRO have inadvertently formed an exclusive club. Others outside the trio may feel powerless to influence events or feed into decisions, which in turn destroys trust.

- Familiarity can breed contempt!

Opportunities for growth and mutual benefit:

- Visit and revisit the conversation about how you all want to work together (as we addressed in principle in a previous article).

- Implement good practice around checking in with each other (about how everyone is and how well the trio members are working with each other).

- Do not assume everything between the trio members is “always good”.

- Leverage on each other’s strengths to minimize duplication of effort.

- Maximize the benefit afforded by role-based skills.

- Learn to have each other’s back. Talk about what this might mean or look like for everyone.

- Be consistent on internal and external messaging. Do not assume. Check-in with the others if in doubt.

- Ensure inclusivity. For example, if two of the trio members have a longer history working together or have been in the company for a long time, there is a need to be aware of this history. The two long timers need to ensure that the last one to join the trio is truly included and not unintentionally left out.

- Really “walk the talk” and borrow good practices from solid leadership development programs - such as giving timely and relevant feedback, taking time to reflect and being aware of one’s own emotions and responses.

- We all know that trust takes time to develop but can be lost in an instant!

Going Deeper

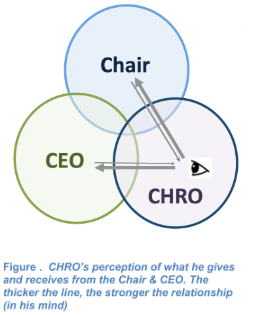

While relationships may be perceived by group members as being close, there are always going to be nuances around these perceptions. A good way to take a closer look is to reflect on what is given and what is received in each relationship.

In Figure 4, the line is slightly thicker for the arrow pointing to the Chair (indicating that the CHRO thinks he gives more than he receives). The pattern is similar for the CEO but for perhaps different reasons, given that the nature of that relationship is different. If we take the view of the CHRO as an example (see Figure 4), he may reflect the nature of his relationship with the Chair in the following manner: “I give the Chair a lot, as I am always ready to respond to her and do so in a timely manner. I also try to anticipate what I think she needs and furnish her with lots of information. I am appreciative of the Chair as she gives me lots of opportunity to interact with the Board. She also gives me warning before any critical issues – where she wants my input – are discussed at the Board.”

Now, if we take the view of the Chair and reflect on the nature of her relationship with the CHRO, the following may be said: “Never before have I given a CHRO so much opportunity to interact and build relationships with the Board. I personally have spent more time with this CHRO than I have in any other Chair post I have held. As such, I really would like to hear more frank and courageous opinions. I would also like to see him taking more initiative around key issues, strategic thinking and about how people are impacted given economic trends facing the business. I’d love for him to be more candid as well as hold a stronger business view.” Looking at the figure above on the right, you will see a thicker “give” line and a thinner “receive” line.

You will note that from the CEO’s perspective (see Figure 5) that the thickness of the lines – give and receive – are similar, though not as thick as the other lines. This differs, in turn, to the perspective of the CHRO. So, differences can abound. The task in hand therefore is how to gain more clarity, so that expectations and outcomes are better matched.

When seeking to improve these relationships, it is critical to ask “what does the other person (in their role) need from me (in my role)? It is also good to have a conversation about how best to work together and to find ways to check-in about this - especially when faced with turbulence caused by adverse workplace conditions.

How best to start?

Start by asking yourself:

- “So…what’s happening for me?” then

- “So…what’s happening for the other person?” and finally

- “So…what’s happening for us all?”

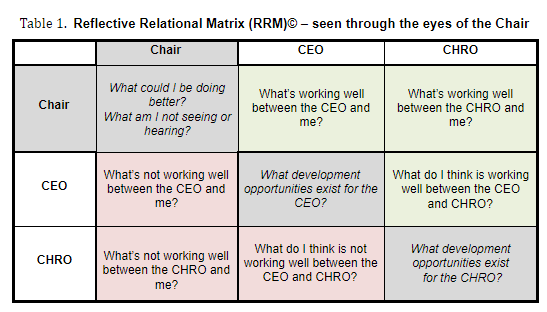

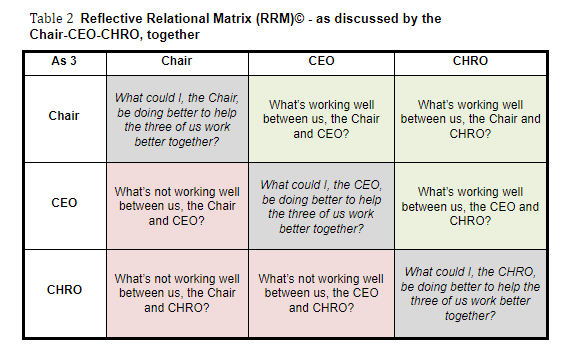

Using a tool like the Reflective Relational Matrix (RRM)© (see Table 1) can help frame your analysis, guide the process of self-reflection and action-taking, and/or create a common focus for the Chair-CEO-CHRO to discuss how they want to work together (see Table 2).

As you may appreciate, one would adapt this matrix for the person using it. Depending on whether you are working with a coach or not, you can also find other questions that may be helpful, for example:

- As Chair, what’s working well for me? What scope is there to improve?

- As CEO, what strengths am I bringing to the role? What could I dial-up? Dial down?

- As CHRO, am I operating exclusively in my comfort zone? Should I deliberately seek a “zone of disequilibrium” where there is more stretch and challenge?

We recognize that the trio – Chair-CEO-CHRO – operates in widely differing workplace contexts and that the contexts themselves will drive what can and cannot happen. Further richness and texture comes into play given that every individual is unique. That said, we believe that there are some core, foundational actions and behaviors that can be usefully deployed by the trio, whatever the organizational context and personalities involved.

Our hope for the trio – at a bare minimum – is that they might work supportively and assiduously to build shared purpose, achieve clarity, create momentum and above all, develop trust. They should champion shared values such as integrity and compassion - and take time to circle back to these on a regular basis to ensure that organizationally, everything is on track. If the trios can achieve this, we feel we can refresh and reframe the saying “two’s company, three’s a crowd” for good.

The time for SuperTrios has arrived. Let’s embrace it.

References:

- Menon, R. (2018), “Management guru Ram Charan says companies need to invest in people, not numbers”, The Economic Times, April 2018.

- Magsig, M & McGrath, J (2019), “Why Now Is the Time to Have a CHRO on Your Board”, White Paper, DHR International, April 2019.

- Groysberg, B., Lee, J., Price J., & Yo-Jud Cheng, J. (2018), “The Leader’s Guide to Corporate Culture: How to Manage the Eight Critical Elements of Organizational Life”, HBR, Jan–Feb 2018.

- Harrington, S. (2019), “Finally, an area of CHRO, CEO and Board alignment: Culture”, ThePeopleSpace, 12 June 2019.